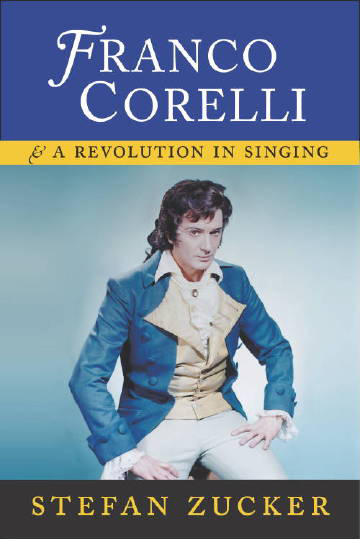

STEFAN ZUCKER: "FRANCO CORELLI & A REVOLUTION IN SINGING" (Bel Canto Society| 2014)

"Zucker is a gifted writer. He needs but a few words to sketch the outline of the Del Monaco-Corelli rift, which forms the starting point from whence the book springs. Perhaps not a very logical beginning, but the book benefits from this introductory punch, a summary of what I myself wrote on their rivalry. What follows are detailed technical explications on squillo, open, covered and closed singing. These signature topics for Zucker’s writing and speaking, serve as insightful leads in introductions to the genealogy of tenor singing from Domenico Donzelli (1790-1873) to the present."

STEFAN ZUCKER

A REVOLUTION IN SINGING

(2014, BEL CANTO SOCIETY, NEW YORK)

A REVOLUTION IN WRITING

This review must begin with the stipulation that I am not your everyday objective reviewer when it comes to Stefan Zucker’s December 2014 publication Franco Corelli & A Revolution in Singing. To begin with, I am a colleague. It was in this capacity that I experienced serious troubles with Stefan at different moments in time. These troubles included Stefan’s attempts at preventing the publication of my Corelli biography, Prince of Tenors. In turn, I have accused him of taking the idea to convert his long announced Corelli ‘biography’ into a book on tenor singing from my own Born to the Breed chapters which have been online for years now. His exploitation of the Corelli/Del Monaco rivalry is based on, or at least made easier by, what he found within the pages and footnotes of Prince of Tenors (the integral Met correspondence and the press articles quoted). Admittedly, this is by no means a forbidden practice. In Prince of Tenors, I quoted from, and even devoted a chapter to, Stefan’s 1990s radio interviews with Corelli, always citing my source. Previously, I also mentioned here a handful of nearly all night long telephone interviews with Stefan while I was in the editing phase of Prince of Tenors, during which we exchanged some fantastic tales. Stefan then boasted of such things as having functioned as the ‘understud of Corelli,’ a claim he actually repeated in some early Amazon pitches for his book, a pitch that also promised us Franco’s ‘1000 lovers.’ Stefan recently told me that his former publisher had done this, admittedly based on some over enthusiastic bravura from Stefan’s side, which he later said he regretted. Up to this point then, a mea culpa… but if his regret is genuine, why does he continue to promise us all these juicy things in his Volume One page 357/8 pitch for Volume Two?

Having read the book now, I must admit that Zucker’s survey of mainly Italian tenor singing in A Revolution in Singing Volume One follows a completely different track than my Born to the Breed chapters. Zucker is a gifted writer. He needs but a few words to sketch the outline of the Del Monaco-Corelli rift, which forms the starting point from whence the book springs. Perhaps not a very logical beginning, but the book benefits from this introductory punch, a summary of what I myself wrote on their rivalry. What follows are detailed technical explications on squillo, open, covered and closed singing. These signature topics for Zucker’s writing and speaking, serve as insightful leads in introductions to the genealogy of tenor singing from Domenico Donzelli (1790-1873) to the present.

From Donzelli to Carreras

A Revolution in Singing follows tenors from Donzelli, Duprez and Nourrit, through De Reszke, Tamagno, De Lucia, Caruso, Pertile, Martinelli, Schipa, Gigli, Lauri-Volpi, Björling, Tagliavini, Tucker, Del Monaco, Di Stefano, Corelli, Pavarotti, and finally to Domingo and Carreras. Obviously, fame and star quality determined the list, and the book sets off the selected singers’ different techniques and merits against each other. Each tenor dedicated chapter contains brief biographical data, along with a clear description of the characteristics of his voice. Tenor chapters from Caruso onward focus increasingly on what Corelli and some others interviewed by Zucker said about the tenor concerned. Thus, it is exactly the book that could be expected, a book based on Zucker’s radio broadcasts and the filmed or unfilmed interview material that he collected through the decades. Being Stefan Zucker, he has no problem labeling people, nor does he shy away from expressing his personal beliefs and tastes. One may even disagree with him, as some contributing writers in his book do. However, these writers merely serve as a vehicle to employ a defensive technique he has always used to his advantage: quote people who believe the opposite. In the section on Lauri-Volpi this technique provided some peculiar input by Gian Paolo Nardoianni. While always seeking the controversial and sensational, Zucker is undeniably also very knowledgeable about the technical details of operatic singing. I particularly enjoyed his insights regarding the uniformity of tenor singing after Caruso among those tenors who employed covering, among them Corelli. Zucker also reveals his own views about the pros and cons of Corelli’s singing. Presented in this coherent way, I found very useful his insights into the impact of various techniques of singing on interpretation. I learned a thing or two from these passages.

The culprit

By means of a less favorable review of A Revolution in Singing on OperNostalgia, my colleague and friend Jan Neckers recently caused a newsgroup flame war that is hard to ignore here. While Jan’s observations are largely correct, I should stress that they do not have to bother anyone in particular. The sexual innuendo, the jokes aimed below the belly on singing with the genitals as photo captions, and the still mild hints at Franco’s love life merely made me smirk. Corelli himself never gave a serious reply to any of the dozens of sexually charged questions asked or puns made by Zucker on air, but you could frequently sense him biting his tongue, in an attempt to stop himself from laughing his heart out. While these incidents add nothing to the content of the book, they are essentially harmless. On one occasion I even have to take blame for being in part the source. This concerns Zucker’s account of Franco’s reported affair with Teresa Zylis-Gara, which derives from a passage in Prince of Tenors about an affair Franco had with a lady I described anonymously as ‘Desdemona,’ in an effort to honor the gentlemen’s code of refraining from naming the lady involved. This, and our 5 or 6 long late night phone interviews in the days when I was editing Prince of Tenors, seem to have induced Zucker to devote an extravagant essay on the subject in Volume Two! The mere announcement of this in his pitch at the end of Volume One has appalled many people who read it. I can only hope that Mrs. Zylis-Gara is proud to see her vocalizing for Franco in private being mentioned as the driving force behind his stamina for a number of years. Despite the physical anomaly that tenor singing above the passaggio is, the ‘technical’ conclusion of all this innuendo in the book can’t possibly come as a big surprise: even tenors have balls!

Having said that, I do wish to stipulate here that the whole fuss about the sexual innuendo concerns no more than one page of a 384 page book. Frankly, I find that I myself already devoted way more attention to this element here than it merits based on a book that has at least 290 more pages devoted to tenors and their various singing techniques (290 rather than the full 384, since indeed we have to deduct a few dozen sales pitch chapters promoting Zucker’s movies and CD’s, although I did find some of the pitches for movies that I did not yet know rather interesting).

As for the 290 pages with what will be for most readers rather dry technical conversation about the selected tenors, they may truly be insightful for singers, operatic journalists and those casual readers who can read music. The average reader, however, will probably have a hard time following pages on mask placement and “eh” and “ah” vowel discussions. These pages are interesting only if you truly would want to take the time to play all the recordings discussed in the context given on each and every page (they were played and discussed in the Opera Fanatic broadcasts). Most people will probably just look up their favorite singers and check their own insights against Stefan’s, which surely can make for entertaining reading, if you are not bothered by the many exhortations to read further about a topic in the still unpublished Vols. Two or Three (I just ignored these exhortations, they didn’t bother me).

On balance

What we have so far:

1. A book on approximately 21 tenors from Donzelli through Domingo, largely based on Zucker’s ‘Opera Fanatic’ radio conversations with Corelli [and some others]. Thus, these interviews finally get an organized presentation in print, where they have been put in their proper context. As Corelli spoke almost exclusively in Italian throughout, Zucker has provided translated transcripts which make Corelli’s comments much more accessible. Where the audio conversations often drifted to all sides, became very repetitive, and ended nowhere in particular, the printed, edited versions Zucker provides make more sense.

2. From Caruso’s entry onward, Corelli, Zucker & guests discuss the technique of the selected tenors, their merits, limitations, and status. As said above, these discussions tend to be rather technical, which makes them more suited to vocal students and singers than to the average music lover who can’t read music. If you have extended knowledge of music or the singers included, you will have many déjà vu experiences. If you lack such knowledge and you have no more than an average interest in these singers, you will find this text surprisingly dry if you had bought it based on the newsgroup discussions about salacious or otherwise colorful content.

3. There is a chapter on vibrato, and there is a lengthy comparison of dozens of Radamès recordings. These will again be interesting mostly to a handful of die hard fanatics and singers who themselves ponder over Radamès. Himself an – extravagant – singer, Zucker does know what he is talking about here. Being a writer active in the operatic arena myself, I personally enjoyed reading many of these explications. I do not agree with everything, but he succeeded in making his arguments clear to me.

4. Whether Zucker is aware of the limited scope of interest in the above or not, I do not know. Neither do I know whether his more controversial inserts of a sexual or other attention grabbing nature (rivalry, madness, Gigli’s anti-semitism, etc.) are deliberate attempts to revive or regain the flagging interest of any given reader who may be tiring of the technical details. It may also simply be his second nature to look for controversy. As mentioned above, it didn’t bother me to the extent that it bothered Neckers, who focused on elements that effectively account for barely 1 % of the text.

5. If Zucker aimed at creating a stir online to increase book sales, he couldn’t have done better. He brilliantly exploited the online rift, to the obvious entertainment of the internet crowd on the sidelines.

6. Zucker is a gifted writer, who spent considerable time also on editing the book. For better or worse, it is certainly a highly individual, and truly inspired book. You can disagree with him, but he is undeniably a man with a mission.

7. The book is beautifully printed and has many photos of all the selected tenors. The printing of the book in this quality also costs real money, which he seems to have raised all by himself. Therefore I have no problems with his explicit pleas for financial support. We all know he runs Bel Canto Society and the man has never, ever published anything without also using the opportunity to promote his sales catalogue – and why not? I do the same in the pdf booklets to my 401DutchOpera.com and 401.DutchDivas.nl downloads [please, visit and donate ☺]. I do this even in my two Corelli-related downloads. These self- promotion pages are in the back of his book, and one can skip through them as one skips ads in newspapers and magazines.

Who’s afraid of Stefan Zucker…

Some of my friends have asked whether I was afraid to take sides in the Neckers versus Zucker polemic online. Allegedly because I was supposedly afraid that in his next volumes ‘Zucker would then attack me in turn.’ Well, let me also stipulate here that the impetus for Zucker’s entire project was to write a book that would prove me wrong (I still have his email stating his intention, although, obviously, since that time his book took off into a different direction). I have nothing to fear from him because the thousands of letters and documents quoted in Prince of Tenors really exist, I spent around 30.000 euros to visit all the places which housed them and I can document my more controversial points with more than unrecorded conversations with X and Y. I’ve had mostly fantastic reviews, among them one by the late John B. Steane, author of The Grand Tradition. I did have an entertaining bad review from a madman on Amazon who dubbed Prince of Tenors a cover up to hide that Franco was homosexual. I could actually have that removed, but it just made me laugh. All this comes with the territory of being a writer in a league that is inhabited by fanatics. I’ve selectively replied to positive, to negative and to silly or unbalanced reviews in our Reader’s Corner section, where I’ve also replied to Neckers’ 2008 review of Prince of Tenors. That’s the new trade: anyone can write about us, but thanks to the internet ‘us’ can now write back, which of course was Zucker’s absolute right in the flame war over A Revolution in Singing (read Stefan's response here). Likewise it was OperaNostalgia’s owner, Rudi van den Bulck’s, absolute right to defend Neckers with a few well placed uppercuts aimed back at Stefan. We are truly all ‘Charlies.’ Once A Revolution in Singing Volume Two is published, I’ll deal with its contents as I find them, including Stefan's incorrect speculations on who did what in Prince of Tenors. Neckers provided materials, and helped me with the historical context of Italy in World War II. He was not in any way consulted on musical matters and is therefore also not responsible for them.

Pasta puttana

Whether Neckers is right or wrong in his review depends on your expectations and your level of appreciation for Stefan Zucker. If you found the ‘Opera Fanatic’ broadcasts entertaining, you will enjoy the book, since it is largely based on the ‘Opera Fanatic’ interviews. If you disliked Zucker’s publications and broadcasts previously, you are likely to be irritated by the same things that irritated Neckers. In my opinion, what Neckers writes is correct from his point of view, but some of his objections precisely underscore Zucker’s strong point: controversy. When Zucker in turn argues that Neckers focuses on sidelines, he has a point. Sometimes various truths exist simultaneously, although I do not wish to turn this argument into a plea for polytheism. Zucker divides the world of the opera buff into pro and con, black and white, and he thrives on that, whether you like it or not. Predictably, Zucker reopens the bogus allegations against Del Monaco in the alleged secual abuse of a minor case, which he serves up with a rich pasta puttana sauce. Next he makes some controversial claims regarding Del Monaco’s La Scala career that are in a number of cases unfounded, simply incorrect assumptions that are unsubstantiated by any evidence. While I can’t prove here that Poliuto was not originally planned for Del Monaco, Zucker in turn doesn’t provide proof for his claim that it was. Perhaps La Scala’s intendant Ghiringhelli was in hindsight a madman. At the same time these more speculative passages largely seem to be limited to his chapters on Del Monaco and Gigli. That Gigli embraced the values of his day in fascist Italy is credible enough, surely nearly all his colleagues did. If Gigli sympathized with the Nazi’s while Italy was an Axis allied power, he was doing what was expected of him. To dub him ‘Hitler’s Tenor’ is as absurd and ill advised as the current Kim Jong-un movie debacle The Interview, but this all comes part and parcel with Stefan. The tendency to stretch a foot into a country mile also goes for the few lines contributed by Robert Tuggle in response to a question on Björling. Those few lines morphed into Zucker’s major sales pitch on the flap of the book’s cover tauting Tuggle had ‘Contributed a chapter to…’ I am not a psychologist and can’t explain Stefan’s need for such name dropping coupled with his odd teasing style promotion (there’s more to follow in Volumes Two and Three). I noticed it, but it did not disturb me as it disturbed Neckers, I just turned to more interesting pages in Zucker’s book, of which there are plenty.

A Revolution in Writing

All in all, this book is classic Stefan Zucker, and I am glad that it is out there. This is not a truncated Prince of Tenors rip off as some other publications I have seen are. Neither is it an amalgam of bits and pieces scraped together from Prince of Tenors and the internet. Zucker’s book investigates tenor singing beginning with Domenico Donzelli from various technical angles. For his methods and insights, some might label it A Revolution in Writing, but I congratulate him on having managed to get it to completion and printed. If I remember correctly, he first announced a book dealing with Corelli about 34 years ago, then still conceptualized as a photo book. I truly hope that A Revolution in Singing Volume One sells enough to cover the costs needed to realize Volume Two, which is where he promises us in depth exploits of Franco’s sex life, including interviews with his lovers (not fans, real lovers), and so on. Now that I’ve read it, I can say that my original reservations about Zucker’s book hardly apply to Volume One, although his pitch for Volume Two suggests that they may still apply there. One never knows, he might eventually tell me that it was ‘just another ill advised sales pitch that slipped through on the spur of the moment.’ If he keeps his promises as made in Volume One, pages 357 through 361, Volume Two will be the first operatic tabloid book, and a veritable Revolution in Writing. Can’t wait to read it!

René Seghers, Febuary 2015

Edited by Claire Winterholler

•

Various reviews of Franco Corelli and a Revolution in Singing

•

Huntley Dent in Fanfare: The Magazine for Serious Record Collectors

"Turn to this book if you want to hear operatic singing spoken of with heartfelt emotion and lifelong understanding. Or, you might be enticed by savory tidbits such as how much Mario Del Monaco was paid for his debut in the 1950–51 Met season ($150), which tenor was consistently the highest paid at the Met (Jussi Björling), and which soprano other than Kirsten Flagstad got the top salary of $1,000 a performance (Lily Pons). There are so many toothsome nuggets that we're consuming a fruitcake that is almost more raisins than cake. Stefan Zucker has earned his place as an encyclopedia of tenor singing. Who else started out in childhood by having Franco Corelli as a babysitter?

But the direct subject, the cake, is equally fascinating. Zucker's adoration for 'the Apollo of bel canto,' as Corelli has been called, is much more than the love of a fan. Himself a tenor and a self-styled opera fanatic- the name of a radio program that Zucker hosted on WKCR-FM in New York for many years- he gives us a Corelli placed in a noble singing tradition: 'Franco tried to combine Del Monaco's fortissimo, Lauri-Volpi's high notes, Pertile's passion, Fleta's diminuendo and Gigli's caress.' Those forebears and many other luminaries are discussed in depth, as indicated by the new book's subtitle, Fifty-Four Tenors Spanning 200 Years.

Zucker makes clear at the outset that this isn't a biography or book of anecdotes. It's one man's theory of how Italian tenor singing has evolved up to Pavarotti and Domingo. Corelli, who was interviewed on the radio for 43 hours by Zucker over the years, speaks in his own voice on many subjects. His comments appear at the end of chapters on specific singers (e.g., Schipa, Gigli, Del Monaco), 11 in all. His astonishing voice and glamorous presence onstage may have diminished some aspects of Corelli that emerge sharply here. He was an intelligent, sober commentator on singing and a serious student of the Italian tradition."

Read the full Fanfare Magazine review here

•

Jan neckers on OperaNostalgia.be

"Author, publisher and editor -all rolled in one- announces this book as part of three volumes which discuss the evolution of 200 years of tenor singing. Now don’t expect a spun out story full of an internal logic which leads from the times of Nourrit to the emergence of Calleja, Florez or Kaufmann. In reality Mr. Zucker tries by hook and by crook to sell the pirated CD’s and DVD’s he produces. Hence, the 34 pages entirely devoted to his commercial catalogue (pages 322 -356). By crook too is the advertisement on the sleeve that announces “Robert Tuggle, Director of The Metropolitan Opera Archives, contributes a chapter on Björling to the appendices”. This “chapter” consists of a grand total of 49 lines concentrating on the tenor’s fees at the Met and in which Tuggle proves that Bjorling was the supreme tenor of his time, in America at least, proven by his fees compared to other tenors and singers at the Met.

I am fairly confident Mr. Tuggle will not be too happy with Mr. Zucker trying to sell his book by implying that a serious researcher contributed “a chapter” on Björling. Another feature (surely well-known to members of Opera-L) is Mr. Zucker’s penchant for titillating sex stories. Up to now few or any opera lovers at all had Mr. Zucker’s eagle eyes which lead him to write in a caption for a well-known innocent photograph of Del Monaco and Caniglia after a performance of Chénier: “Did he really sing with his genitals in that position ?” The second volume in this series surely promises to be most interesting as Mr. Zuckers promotes this book-to-be-published with a so-called Franco Corelli quote: “People assume that in old age I am hearing Verdi and Puccini in my mind’s ear. No! The music I am hearing and that keeps me going is the sound of Teresa Zylis-Gara having orgasms.”"

Read the full OperaNostalgia review here.

Read the various reactions to this review on Opera L here

•