|

As I once wrote in the Dutch Music Magazine Luister, one may compare opera with religion. Both have believers in various Gods, and using only Christianity as an example, there is a striking parallel between BC and AD. The watershed year in opera is 1837, when Gilbert Louis Duprez gave the world 'Il Do di petto' – the high C from the chest. Ever since, tenors have reigned in the operas of Donizetti, Verdi and Puccini. However, along with their enhanced status, their worries also increased. Ever since Duprez, it was 'all or nothing', especially for the rare breed of dramatic tenors in Italian opera, of whom only a handful have truly succeeded in the last 170 years. After Duprez, perhaps only Antonio Aramburo, Francesco Tamagno, Giovanni Zenatello, Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, Mario del Monaco and Franco Corelli whose throne has been vacant since he gave up the stage in 1975 (except for some brief returns in 1976 and 1981).

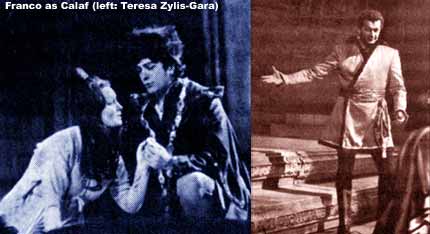

As within any religion, some might argue about the latter statement, saying that later tenors like Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo or even the young José Carreras made very successful recordings of Corelli's hallmark operatic roles from Calaf in Turandot to Manrico in Il trovatore.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notwithstanding the truth of this claim, it must be noted that there is a big difference between a successful studio recording, where notes can be recorded separately (they can even be artificially pushed up to a higher pitch this way) and a successful performance on the stage. Captured in live recordings, Domingo certainly matches Corelli's timbre in beauty, Pavarotti equals him in sheer vocal brilliance and Carreras matches his ardor. Moreover it would be hard to deny that any one of The Three Tenors easily surpasses Corelli in sheer musicianship: they hardly ever cross the line of good taste whereas Corelli indulged in a number of bad habits. Perhaps the worst is his lisping on certain consonants, although he himself argued that this was nothing more than an intrinsic feature of the language as it was spoken in his hometown. Then he had the habit of attacking the notes from below, which (especially in studio recordings) could sometimes give the impression that he was dragging the notes. He indulged in lingering on high notes ad absurdum: fans clocking the seconds he held his 'Vittoria!' in Tosca were never disappointed. And after he mastered the art of the diminuendo and fil di voce, one could argue that he gradually turned it into sheer vocal exhibitionism, spinning out 'disciogliea dai veli' in 'E lucevan le stelle' beyond the point of disintegration.

Nevertheless those are still remarkable vocal achievements, as his voice, like the voice of Mario del Monaco, was primarily a forte instrument. It adds to his glory that he did not content himself to be or to become another Francesco Tamagno or Del Monaco, but instead sought to master the art of belcanto completely, including the pyrotechnics one would usually reserve for a tenore di grazie. Moreover from 1958|59 onwards he managed to equalize his instrument, subduing its pronounced vibrato (comparable to Lauri-Volpi's vibrato in his younger years), which added an intrinsic lyric quality to his voice. This gradually made the instrument suitable for the romanticism Corelli sought to interpret in later years: Roméo, Werther and Rodolfo in La Bohème! Taking all this into consideration, one might argue that in Corelli's art two worlds unite: the imaginative belcanto world of his predecessors Enrico Caruso, Aureliano Pertile, Beniamino Gigli and Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, upon whose recordings he used to shape his voice on the one side, and the world of modern opera where conductors watch over composers intentions on the other. In his best moments these worlds merged to splendid effect.

The Corelli miracle

On the other hand, characteristics like anachronistic, uncontrolled, exhibitionist and easily-carried-away are not usually linked to greatness. Still, many consider Franco Corelli to be unsurpassed. Not surprisingly perhaps, if one understands that the vocal acrobatics described above can only be mastered if one has the technique and the vocal power to do so, especially in the high register. Not surprising then, that he was ever grateful to The Muse that blessed him with an exceptionally large, dramatic voice and the willpower and good fortune to develop it into a colorful and powerful instrument. And there is more to the Corelli miracle. Like that of all great tenors, his voice was immediately recognizable, unique in color and endowed with the squillo to fill the world's largest auditoria, be it the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, the Teatro San Carlo in Naples or the Arena di Verona. But his best quality, if one can dub this a 'quality', was the sheer beauty of his timbre: dark, yet glowing like melting bronze, vibrating, radiant and rising to the top of the scale like a straight pillar of sound, never diminishing in power. Many singers can boast one or two of these qualities, but how many have ever combined them in a single voice?

Domingo, Pavarotti and Carreras recorded Calaf successfully, but there are far fewer live-performances of the part to be seen in their chronologies, and where these were recorded two of The Three Tenors usually takes the safe route, eschewing the optional high C in the stellar phrase 'Ti voglio ardente d'amor' for the lower alternative of 'Ti voglio 'tutte' ardente d'amor'. Moreover I have reviewed many a DVD from the seventies up to the present day where singers seem to wake up only just in time to save the performance halfway through Act III – not so in Corelli's world. Among the hundreds of private live recordings I heard of him he is always completely into the action from the moment he steps on to stage. As the hero in love, in agony or despair he convinces chiefly through vocal sincerity. No wonder then that Corelli's live recordings enjoy a legendary reputation, culminating in the present boost of interest. For years, the number of labels and the number of issues of his performances easily surpassed the number of live recordings of any other tenor that ever recorded, except perhaps Giuseppe Di Stefano, who caught up with Corelli in recent years also because there aren't much Corelli recordings left to be discovered. Corelli is the unchallenged champion of MYTO, Living Stage, Opera D'Oro, Opera Legacies and a number of private labels that jumped on his recordings after simple home made copies of unpublished Corelli-performances sold at over $ 200 on auction sites – and that hysteria already started in the year before he died!

The Corelli career

Unlike his private life, Franco Corelli's career is well documented in books and chronologies. His emergence as the world's leading tenor was achieved in remarkably little time, although his arrival on the operatic stage took place rather late in life. Born on April 8, 1921, his debut in a Spoleto Festival Carmen occurred as late as August 16, 1951 when the tenor is over thirty years of age. All the more remarkable since he had little vocal education. Initially it was his friend, the baritone student Carlo Scaravelli who encouraged him to enter a vocal competition in Pesaro, where Corelli's voice was noted as promising, but in need of further study. This was achieved by waiting in Ancona for Scaravelli to return from his classes in Pesaro, where the baritone told the future tenor what he had learned (Corelli briefly even tried training as a baritone at some point). Interesting enough Scaravelli's teacher appears to have been Maestro Arturo Melocchi, the teacher of Mario del Monaco whose specialty was the technique of singing with a lowered larynx. Although Corelli later admitted to having met Melocchi in person as well, he maintained that these meetings were only sporadic. The other half of Corelli's vocal education was made up tuning in with the recordings of his favorite singers, which proved to be insufficient to enter classes in the Spoleto 'Centro Lirico Sperimentale' competition of 1950. In May of the following year he tried his luck once more, singing 'Celeste Aida'. This time all went well and he was admitted, which meant he had to prepare for his stage debut in Verdi's Aida. The four months until August were spent attending regular classes, but these proved to be insufficient to turn the promise of the single aria into a complete performance. Corelli felt insecure in the technically difficult part of Radames and at last minute it was decided to stage Bizet's Carmen instead, where the young tenor was more at ease.

His debut as Don José was immediately recognized as a promising one. Naturally his shortcomings did not go unnoticed, but his generous vocal resources indicated a possible great future. At this point it is interesting to observe that although Corelli had to ripen in the Italian provinces like any other beginner; his appearances were not at all with provincial casts. From July 1952 onwards he seldom appeared next to lesser artists than Maria Caniglia in Adriana Lecouvreur, Pia Tassinari or Giulietta Simionato in Carmen, Boris Christoff and Miriam Pirazzini in Boris Godunov and Guerrini's Enea, in which he was also flanked by Antonietta Stella. Immediately after the Enea world premiere came his first encounter in Norma, with the already notorious Maria Meneghini Callas. The location of this historic encounter was the Rome Opera and the dates were April 9, 12, 15 and 18, 1953. The months following saw highly successful appearances as Pierre Besukov in the world premiere of Prokovjef's Guerra e pace and as Canio in Pagliacci. The year 1953 was crowned with his first Radames in Ravenna's open-air theatre, where he avenged himself for the cancellation at Spoleto two years earlier.