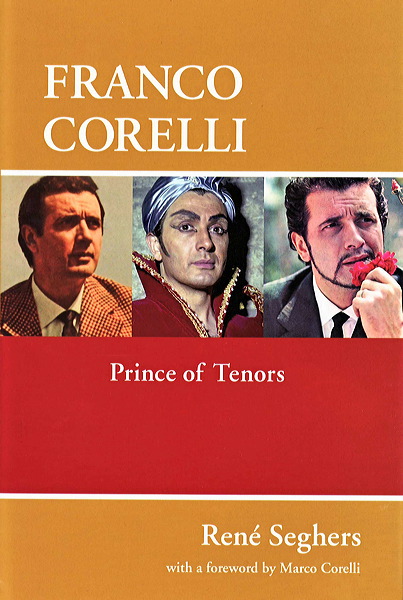

René Seghers "Franco Corelli | Prince of Tenors"

(English language | 2008, Amadeus Press)

(New York, Amadeus, 2008. 526pp. Index; Bibliography; Exhaustive Chronology; 100+ Photos);

INDEPENDANT CRITIC REVIEWS

"With the operatic world at his feet, Corelli's insecurity was such that at times the fate of this whole world seemed to hang on a feud with the dentist, the health of his pet dog, the inadvertent reference to a rival tenor. The omnipresent wife, watchful and vociferous, is both the guardian of sanity and the promoter of farce. Sometimes it seems that life offstage is a demented extension of the absurdities on....In the midst of all this it must be said that there is one person who keeps his reason and preserves a fair sense of balance, and that is the author. Corelli is a very emotive subject....as we follow him in the late chapters of his book we realise that we are going to care a great deal what becomes of this extraordinary man as his decline approaches....There is a genuine human involvement in this book."

"With the operatic world at his feet, Corelli's insecurity was such that at times the fate of this whole world seemed to hang on a feud with the dentist, the health of his pet dog, the inadvertent reference to a rival tenor. The omnipresent wife, watchful and vociferous, is both the guardian of sanity and the promoter of farce. Sometimes it seems that life offstage is a demented extension of the absurdities on....In the midst of all this it must be said that there is one person who keeps his reason and preserves a fair sense of balance, and that is the author. Corelli is a very emotive subject....as we follow him in the late chapters of his book we realise that we are going to care a great deal what becomes of this extraordinary man as his decline approaches....There is a genuine human involvement in this book."

John Steane, GRAMOPHONE, Sept., 2008

"This is the second biography of Franco Corelli to be available in English. The first, subtitled "A man, a voice", by Marina Boagno, an Italian novelist, was first published in 1990, the English translation appearing in 1996. In terms of its main function it was a disappointing piece of work. Largely a fanzine, with a patchwork structure which neglected essential areas of Corelli's life such as the years prior to his operatic debut and his relationship with Loretta di Lelio, it largely consisted of reviews of his performances with the author's comments on them. A revised edition was produced after Corelli's death in 2003 which reportedly fills some of the more glaring omissions of the original publication, though at the expense of losing some of its most valuable elements; I have not read the revision, but, in any case, the present book under review satisfies the need for a biography of this important artist admirably.

It is a scrupulously researched, chronological account of Corelli's life, which, while palpably on the side of the singer, sets exemplary standards of objectivity and comprehensiveness. In the 1960s and early-70s it was fashionable for British music critics to sneer at the two major Italian tenori di forza, Mario del Monaco and Franco Corelli. The former, I learnt, for these were my formative years as a student of opera, was monotonously stentorian; even if his ramrod-powerful delivery was acceptable as Otello he was contemptibly unable to adapt his voice to the requirements of lyric roles. Corelli was a shameless crowd-pleaser, who exploited the natural emotive quality of his voice and its colossal size to arouse the cheapest responses from audiences, especially in the United States, towards whom British critics were notoriously condescending. No serious operatic critic of that time or for some years beyond would risk the ridicule sure to descend on his head were he to defend Corelli or admit to being swept away by the glory of his sound. In the last few years, however, while opinions on Del Monaco have hardened, Corelli has begun to undergo a discernible re-assessment. Re-issues of his recordings have brought the realisation, often shame-faced but nonetheless spontaneous and sincere, that there was more to Corelli than a voice and the words "interpretation" and even "style" could in fact be applied, without distortion or embarrassment, to his recorded performances.

René Seghers's book is well-timed for this reason and for another more urgent one. The book benefits from very little direct personal testimony from its subject himself: just a single interview, a follow-up being prevented by Corelli's serious heart-attack and the abject decline into dementia that followed it. He did, however, benefit from the co-operation of the singer's cousin Marco Corelli, who had withheld his assistance from previous writers but who saw in Seghers a seriousness of intent and a commitment to tell the complete life-story of his relative, with proper emphasis being assigned to vocal development, personal and professional relationships and the years on either side of the period when he earned the nickname in America of "Mr. Soldout". The standard of research that impressed him is precisely what makes this biography superior to its predecessor.

Seghers fills in the background of the family's musical connections with just enough relevant detail but without labouring the point: his grandfather was a comprimario tenor, his uncles Corrado and Viero deeply involved in local choirs and his brother Ubaldo (known familiarly as "Bibi") a professional baritone. The conditions of a fascist state, with its indoctrination of young people and the impact of its anti-Semitic values on Corelli's native city of Ancona, with its large Jewish community, are reflected without receiving undue emphasis. For the first time Corelli's second love, his intense relationship with Iride Monina, is charted and its demise attributed to jealousy. The repercussions of childhood incidents on Corelli's later psychological development are reported.

An influential character who appears constantly throughout the book is Carlo Federico Scaravelli, who emerges as the first to recognise the potential of Corelli's voice, is responsible for his first lessons, accompanies him to the Pesaro Conservatory, from which he is soon excluded, and acts as intermediary in passing on vocal guidance from the teacher Arturo Melocchi. They later audition together for Ghiringelli at La Scala before Scaravelli decides to set limits to his own ambitions.

Seghers's tracing of Corelli's burgeoning career goes back even before its start, with an analysis of some private recordings made in 1950, one of them, a duet from "La Gioconda", with brother Bibi. The unruly nature of the top notes is noted. Corelli's triumph in the Spoleto competition and his debut there as Don José in 1951 led to the offer of a contract from Rome Opera. The surprising thing about the Rome years is the range of operas in which Corelli sang: Zandonai's "Giulietta e Romeo", "Boris Godunov", "War and Peace", "Iphigénie en Aulide", "Giulio Cesare" and two premières, "Enea" by Guido Guerrini and "Romulus" by Salvatore Allegra. In addition, at the Maggio Musicale he appeared in "Agnese di Hohenstaufen" and at La Scala in "La Vestale" and "Eracle" (Handel's "Hercules"). Evidence of the size of the voice in those early years is provided by the number of his open-air appearances, many of them in the role of Don José. Corelli's rise was rapid, though it must not be forgotten that he was already 30 when he debuted in Spoleto. Within two years he was Pollione to Maria Callas's Norma, which marked, as Seghers puts it, "the point at which the usual encouraging reviews are exchanged for unqualified praise of the young tenor's talents."

Seghers has been extraordinarily energetic and fastidious in seeking factual detail for his portrait. His footnotes refer to a vast number of letters from, and interviews and telephone conversations with, surviving family members and friends on personal matters, while the professional colleagues contact with whom he has informed his narrative include Anita Cerquetti, Giulietta Simionato, Gabriella Tucci, Magda Olivero, Antonietta Stella and Birgit Nilsson. Cerquetti was due to sing Aida with him as his debut role in Spoleto, though the opera was changed to "Carmen", while he was Don José to Simionato's Carmen at several venues in the first few years of his career, so we get from their testimony revealing insights into the state of Corelli's voice and temperament at the start of his career.

This wide-ranging archaeology has unearthed unexpected ephemera, such as Italian Radio telecasts from the 1950s and romantic tele-novels in which the singer starred as hero. First-hand contributions from Corelli himself are embodied in the conversations with him broadcast on radio in the USA in the "Opera Fanatic" series and numerous interviews he gave to the print media.

Access to the correspondence between Rudolf Bing and his adviser on voices Roberto Bauer enables Seghers to interpret the relationship between Corelli and the Metropolitan Opera. From the correspondence we learn of the brinkmanship, the bluff and counter-bluff indulged in repeatedly by both sides in an attempt to strike the best deal, complicated by the rivalry with other tenors, competition for the singer's services between the Met and La Scala and tax laws in the United States. Haggling over a mere fifty dollars and built-in payments for unsung performances are just two of the peculiarities that characterise the negotiations described here.

Bing was initially unimpressed by Corelli and his disdain persisted as late as 1958 when he wrote in a letter to Bauer "I do not like Mr. Corelli's singing ... I think he is unmusical and conceited and that his voice is not very good". For Bing, however, economics came before art. An important sub-plot is the feud between Corelli and the tenor whose status he was threatening as leading tenore di forza, Mario Del Monaco. According to the older tenor's son Giancarlo Del Monaco, it was Mario's brother who invented the jibe "PeCorelli" – Corelli the Sheep – referring to Corelli's then pronounced vibrato, which was taken up by pro-Del Monaco claques at various theatres where Corelli performed to embarrass him. Franco Corelli seems to have ceased worrying about the rivalry by 1959, according to a contemporary interview in "Oggi", and Giancarlo is quoted as blaming its perpetuation on Corelli's wife Loretta, for whom it was effective PR. Certainly Bing and Bauer had no hesitation in playing one tenor off against the other. The well-known scandals surrounding Corelli are not ignored: the missed rehearsals, the cancellations, the tantrums, as well as the news headlines that he attracted. Among these are the sword-fight with Boris Christoff at rehearsals for "Don Carlo" at Rome Opera in 1958, the "Battle of the Boots" at La Scala in 1959, with himself vying with Jerome Hines to be the tallest through the enhancement of the heels of their respective footwear, and the contest of held notes in a 1961 Boston "Turandot" and the alleged biting of Birgit Nilsson which followed it, an outcome which is denied.

Corelli's somewhat wayward, even laddish youth, during which he preferred sports and physical activity to academic study, might seem to be the prelude to an account of a playboy lifestyle. In fact his only real vice seems to have been fast cars. His wife Loretta is generously treated. The extreme domineering behaviour described by Eileen Farrell in her autobiography is under-played, with much greater emphasis being given to her involvement in exploiting the media to cultivate her husband's image. Seghers has discovered a large number of newspaper and magazine articles that show this process in action. If too much space is devoted in the book to detailed quotations from their recipes for family meals, then at least they are a reflection of how cookery was used as a PR tool. Their private life remained private and self-sufficient. There was no entourage of hangers-on and consequently there could be no "Kiss-and-Tell" stories to smear their reputations or obscure their musical record.

As far as technical issues surrounding Corelli's vocal production are concerned, Seghers is a little prone to use the impenetrable jargon which writers on singing and singing teachers favour but he is clear about the effects of Corelli's studies with Giacomo Lauri-Volpi: the addition of a lyrical element which permitted him to take "La bohème" into his repertory in 1964, the upward extension of his range and the general improvement in the singer's self-esteem. The author is right to point out Corelli's ability to spin out a line and the acquisition of a magical diminuendo from the mid-1960s, whatever the source of those added dimensions to his singing. He is quite objective about the singer's musical faults. He picks his words carefully and wittily in thus describing Corelli's undeniable vocal mannerisms: "He frequently indulges in excessive use of portamento and scoops to get back in line when he remembers that somewhere out there an orchestra is waiting for him." One feels throughout, nevertheless, that he surrenders to the glory of the sound. There is no doubt that Corelli did improve vocally and develop as an artist, in addition to which he terminated his career in a well-timed pre-emptive strike against vocal decline.

Tantalising glimpses of what might have been are evident in the accounts of discussion and planning for productions (Manon at the Met and an "Otello" conducted by Karajan and directed by Olivier!) and recordings ("Otello", "La forza del destino", "Manon Lescaut", "La Fanciulla del West"). For the correspondence with EMI, Seghers received extensive co-operation from Tony Locantro at its London headquarters.

There is no chronology or discography but well-nigh-perfect examples of both are available thanks to the meticulous work of Frank Hamilton (link below). The original Boagno book had a magnificent 80-page section of 120 black and white photographs. Seghers has included many more, embedded in the text, which reflect the singer's private life as well as career. The drawback to some of these is that they are very small. Each performance and recording has a panel in the text giving date, location and cast details.

This is as estimable a biography of a singer as one could imagine. Authors of such works often find it hard to resist partisanship and few have approached their task in as scholarly a way as René Seghers. Now that it is no longer infra dig to admit to the power of this most visceral of singing voices to arouse the sort of emotional reaction which opera composers intended, the book deserves a wide and appreciative audience.."